Why Did Some Criticize Fdrs Art Programs While Some Defended Them?

Ever since arts institutions went into a tailspin at the very offset of the pandemic-induced economical stupor last year, commentators everywhere have invoked the example of the New Deal art projects in proposals to address the crisis. William S. Smith, so editor of Art in America, reached for the history every bit early equally last March in a stirring phone call to action. This Jan, the New York Times'south ace art critic Jason Farago did the same. Even more than significantly, a host of Democratic mayors put out a letter of the alphabet recently calling upon the newly minted Biden administration to expect to the example of FDR's New Deal in supporting the increasingly drastic culture industries.

It makes sense. The New Deal is our brightest-shining example, in a country with no social democratic tradition, of directed government intervention into the economy in the face of crisis. Still I experience a lot gets left out in these appeals to the instance of the New Deal art projects. Without filling in the nitty-gritty of the history that impelled the United states's singular experiment with regime arts patronage, I get the sense that we are calling people into battle without arming them for the fight.

The Origin Myth

Cover of Fourth dimension magazine, September 5, 1938, featuring a story about Holger Cahill and the Federal Arts Projects.

There is a kind of mythic origin story for the New Deal art projects. It goes something similar this: In May of 1933, the painter George Biddle, an old school chum of Franklin Roosevelt, wrote the newly elected president a letter of the alphabet.

Biddle mentioned the then-current mural renaissance in United mexican states, adding that "Diego Rivera tells me that it was only possible because [president Álvaro] Obregon allowed Mexican artists to piece of work at plumbers' wages in order to express on the walls of the government edifice the social ideals of the Mexican Revolution." Young Usa artists, Biddle wrote, "are witting every bit they never have been of the social revolution that our country and culture is going through and they would be very eager to limited these ideals in a permanent mural art if they were given the government'southward cooperation."

FDR forwarded the letter to Harry Hopkins, his head of federal relief programs. Art initiatives were worked into the welter of relief schemes, and the residue is history.

That's an highly-seasoned narrative. It fits the ingrained bias of artists and intellectuals towards individualistic narratives focused on elite benignancy. History is spoken of as if information technology is a matter of people coming up with nifty plans that kindly technocrats then execute for you lot.

Yet Holger Cahill, who would go on to caput Federal 1, the near celebrated of the New Deal art projects, doubted this tale. Hither is what he said on the matter to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art (the last sentence is a fragment because information technology is every bit oral history):

Who actually started this? Now, when people write about this thing and when George Biddle writes almost it, he claims that he did it because he knew Roosevelt at Groton and at Harvard. Well, I'chiliad not so sure of that, and actually I don't believe it because at that place were then many people—the terrible excitement about the unemployment and the possibility of our programme, which nobody had ever envisaged in this country.

Every bit Shannan Clark puts it in a more scholarly register in the just releasedThe Making of the American Creative Form: "Although information technology may be tempting to see the WPA cultural projects as part of the inexorable expansion of state capacity during the Roosevelt administration, pressure from leftist activists was disquisitional in overcoming the skepticism that many New Dealers harbored regarding relief employment for culture workers."

The Crisis for Culture

Pamphlet is support of the End Poverty in California (EPIC) motility.

What does that mean? Our country has (rightly) been transfixed since January 6 past the spectacle of a disheveled gang of right-wing expressionless-enders, encouraged by Donald Trump, attacking the nation's Capitol. That sordid carnival has essentially inverse the political conversation. I has to understand, however, that for the political institution and public alike, the spectacle of the 1932 election—taking place years into a brutalizing economical collapse—was even more than transfixing.

As Hooverville camps of the destitute went up everywhere, masses of unemployed WWI veterans and their families occupied the Anacostia Flats in Washington, D.C., demanding the immediate payment of a promised "bonus" payout from the government. As the ballot approached, Hoover decided to shoo the and then-chosen Bonus Army abroad from the seat of government. The news reels lit up with footage of a trifecta of hereafter Globe State of war II generals MacArthur, Eisenhower, and Patton leading bayonet charges against penniless vets through clouds of tear gas, incinerating their last holding.

The sense that order had reached a humid point, that a showdown between masses and rulers was imminent, impelled the first years of the FDR administration. It besides radicalized the nation's cultural workers.

The widely debated 1932 open letter of the alphabet, "Civilisation and the Crisis," direct referenced the violence against the Bonus Army as a sign of the descent of the U.s. into a crisis that its capitalist class was not equipped to deal with. The essay-statement, signed by cultural luminaries including Sherwood Anderson, Countee Cullen, John Dos Passos, Langston Hughes, and Edmund Wilson, triggered widespread debate and a rethinking of solidarities among artists. Only its immediate mission was equally a pitch for the League of Professional person Groups for Foster and Ford—that is, it was in support of the Communist Political party United states in the '32 election.

While Herbert Hoover is draped forever in righteous contemptuousness, FDR is at present so sanctified in progressive mythology that it may inspire a double-take to read the intellectuals' view of him in '32 every bit a typically two-faced political operator: Roosevelt "has promised progressivism to progressives and conservatism to conservatives. He has promised to lower the price of electric power without lowering the inflated value of power visitor stock. He has promised more and less regulation of the railroads."

The tone was probably in advance of mass sentiment, the product of a Communist Party then under the influence of Moscow's freakishly sectarian and delusional claims that the final revolutionary battle was at mitt. But it does illustrate the urgent disillusionment amid influential cultural layers, looking for an outlet. Two years later, the same unsparing frustration was expressed in Langston Hughes's bitter poem, Ballad of Roosevelt: "The pot was empty / The closet was blank. / I said, Papa, / What's the matter hither? / I'm waitin' on Roosevelt, son, / Roosevelt, Roosevelt, / Waitin' on Roosevelt, son."

Another example in bespeak: In '33, The Jungle author Upton Sinclair published I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future. Capturing the desperate hunt for whatsoever narrative of salvation, this bestselling novelist's picture of cooperativist government inspired his real-world Terminate Poverty in California (EPIC) movement, a socialist-ish grassroots electoral uprising.

Sinclair came seriously close to winning the governorship. FDR assured him of his sympathy in private and refused to endorse him in public. The bigfeet of California industry, including the Chandlers and Warners, unleashed a tidal moving ridge of dirty tricks and scare-mongering media—including a threat to move Hollywood to Florida should Sinclair win—to brake the momentum of the insurgent EPIC motion.

The signal is: The main event of US cultural life at the time wasn't Biddle'southward glad-handing. It was deep radicalization amid cultural workers who were pulling hard left under the influence of the Depression and weren't inclined to "wait on Roosevelt" very long at all.

The Scope of the Projects

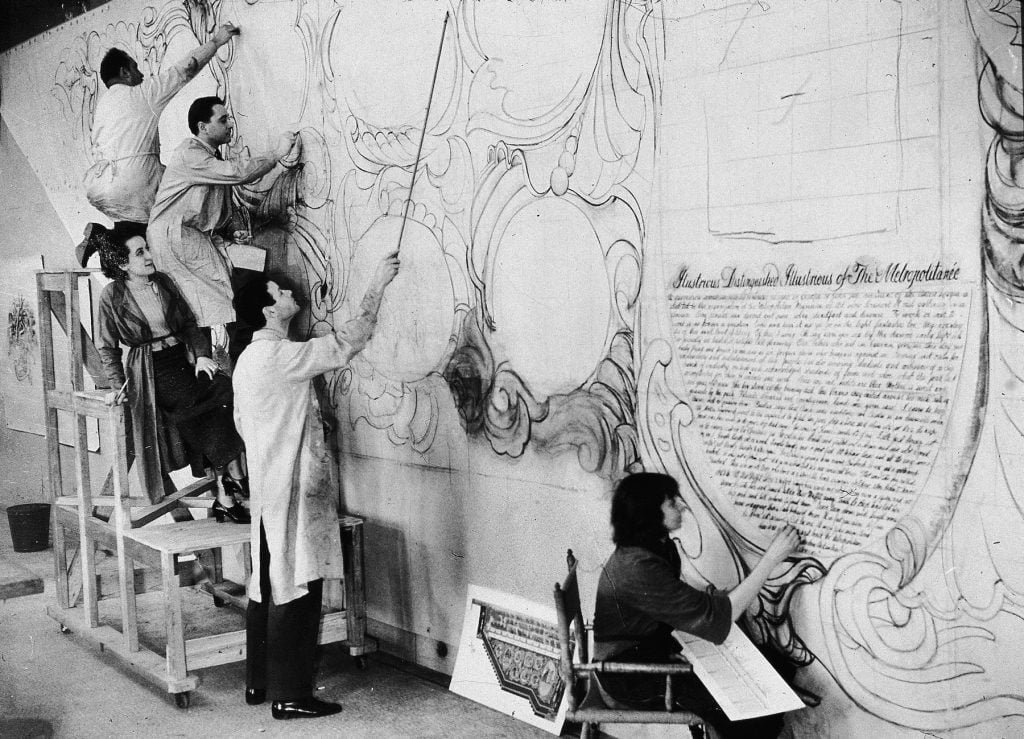

American artist Allen Saalburg directs WPA artists at work in a temporary studio at the American Museum of Natural History on murals commissioned for the Armory Building in Central Park, New York, New York, 1935. (Photo by New York Times Co./Getty Images

The New Deal Arts Programs unfolded in two phases. The earlier programs, most notably the Treasury Department and the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), synthesized with FDR's public works programs in what y'all call the Commencement New Bargain, the early patchwork of emergency economic relief measures. They focused on placing artworks in public buildings and government-funded projects. They operated via juried competition, and had a more than or less conventional idea of the artist's office in club.

The more famous part of the New Bargain Arts Programs emerged from what you call the Second New Deal, the mid-'30s initiatives done under the pressure of what amounted to a nationwide labor uprising led by organized political radicals of various kinds, including full-calibration, metropolis-paralyzing general strikes in San Francisco, Toledo, and Minneapolis, all in 1934. This is idea of as the most radical portion of the New Bargain, the period of large-scale regime piece of work relief nether the Works Progress Administration, begun in '35, which incorporated directly employment of thousands of artists, actors, musicians, and writers every bit hired employees.

The New Deal fine art projects seeded important parts of the US fine art mural which would deport fruit later. Jackson Pollock, too poor to travel to his own begetter'south funeral and working equally a janitor, would spend 8 years with the Federal Art Projection'southward mural and easel divisions. He wasn't eligible for the earlier arts projects like the PWAP because these required proof of skill as an creative person or instructor, which he did not yet take.

The 2nd New Deal'southward focus on demand saved him.

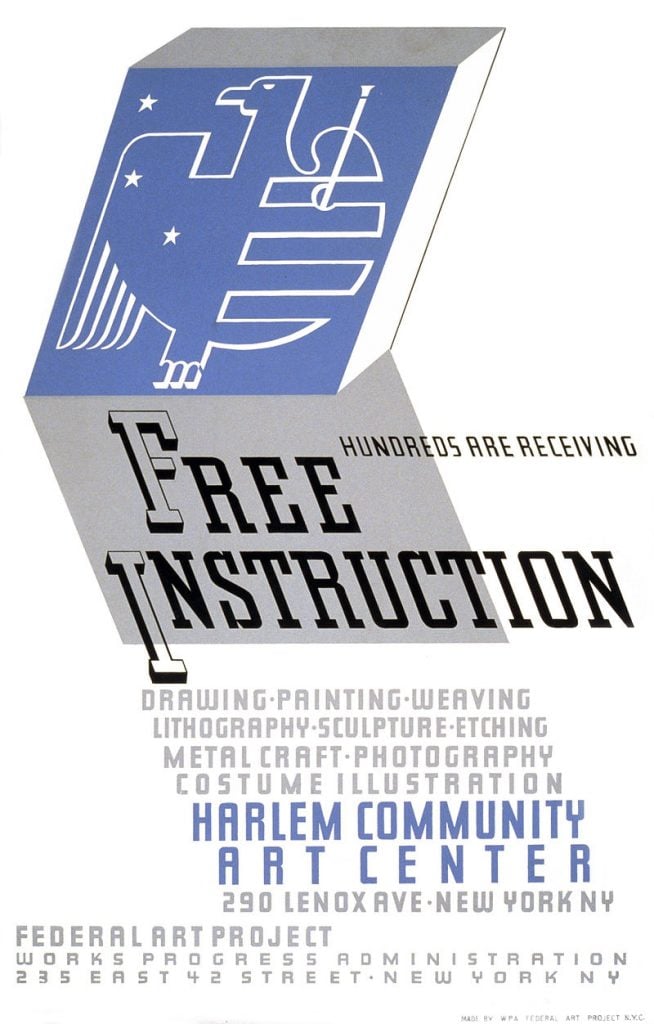

Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko were all WPA beneficiaries—though since none were US citizens, they were all terminated amid a moving ridge of anti-immigrant backfire in '37. Alice Neel worked on the WPA; so did Louise Nevelson. Augusta Savage ran the Harlem Community Art Center, sponsored by the WPA. Among her students was Jacob Lawrence.

Affiche for the Harlem Community Art Center (1938).

The young Charles White, recently and so celebrated, got his start on the WPA's Illinois Fine art Projection (IAP) in Chicago. He became a lifelong radical in part because of the sit down-ins he participated in to get more Blackness artists hired by the program.

"My commencement lesson on the IAP project dealt non so much with paint as with the role of unions in fighting for the rights of working people," White would recall afterwards.

Artists Get Organized

Diego Rivera addresses a protest at Columbia Academy shortly after his commission for the Rockefeller Heart Murals was cancelled, 1933. (Image courtesy Getty Images)

The very day that George Biddle penned his letter to Roosevelt—May 9, 1933—Diego Rivera had his contract terminated past Nelson Rockefeller for his Man at the Crossroads landscape at Rockefeller Center, due to the Mexican muralist'southward insistence on including an image of Lenin. (Rivera was probably in the mood to make a argument, having merely spent down some of his socialist cred doing the Detroit Industry murals for arch-backer Henry Ford.) Artists rallied to Rivera's cause, forming the Artists Committee of Activity, which would become part of the ground for the Artists' Union that would agitate for regime hiring of artists and and then organize the Federal Art Projects.

The other component that fed into the Artists' Union was the Unemployed Artist Group (UAG), organized out of the John Reed Clubs, a Communist Party-sponsored concatenation of nationwide community art centers that amounted to an embryonic, alternative left-wing art earth. Hundreds of UEG members swarmed the College Fine art Association in October of 1933 to demand work relief for artists, petitioning and putting active pressure on officials similar Hopkins.

It was thanks to such collective arrangement that the arts projects would be shaped into the unprecedented class that they ultimately were: every bit economic relief for hungry artists rather than the more conventional type of commissioned state patronage. When Julianna Strength, director of the newly minted Whitney Museum, was put in charge of the New York City region, the UAG led protests at the museum to demand that the program would focus on demand rather than just awarding established successes. That pressure worked.

Y'all actually have to capeesh the audacity of artist organizing in this period. Artists were hired as unemployment relief, yet they had the spine to insist that they would be treated with respect and were owed dignified atmospheric condition (it should be noted that pay was e'er more meager than the hoped-for "plumbers wages"). Where, in the midst of such historic economic desperation, did this unexpected reservoir of self-confidence come from?

Equally fine art historian Andrew Hemingway puts it, the answer is not hard to find: It was the larger phenomenon of a mobilized and militant working class. "There was a existent homology, partly grounded in direct imitation, between the rank and file energies that led to the not bad sit down-downwards strikes of the flow in Flint, Detroit, Akron, and elsewhere, and the sense of mobilization and collective solidarity among artists."

The Counteroffensive

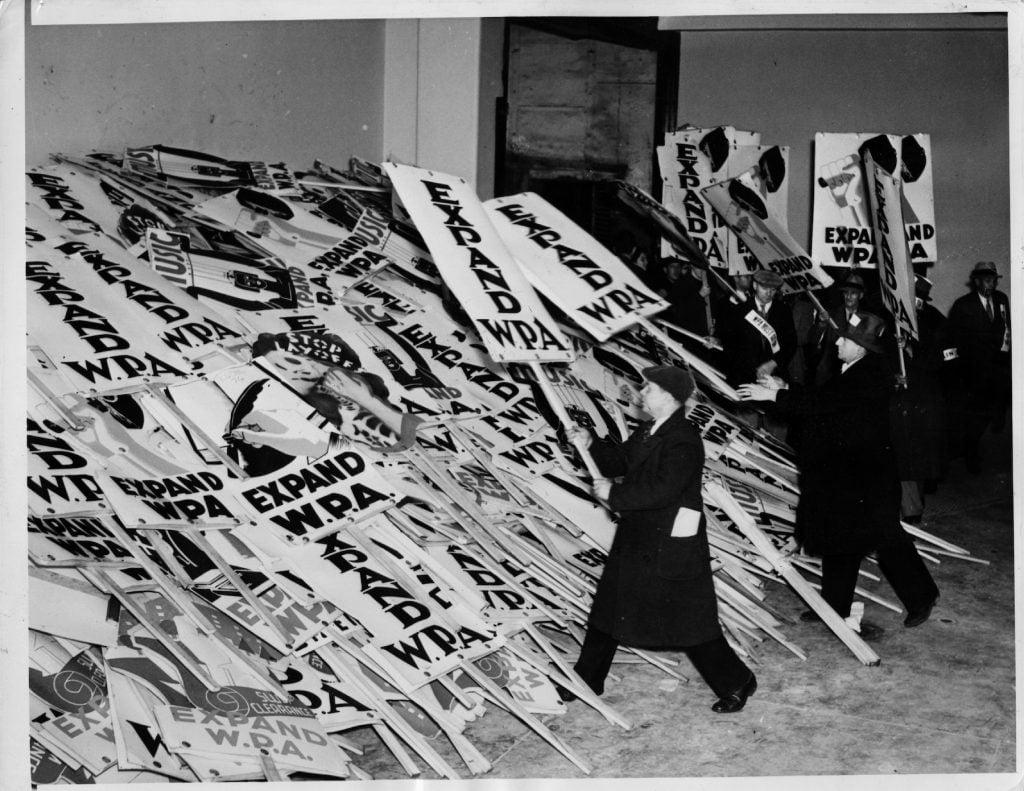

A crowd protests the curtailment of the WPA and piles picket signs outside Madison Square Garden. (Photo past Hulton-Deutsch/Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images)

Simply you lot must as well understand that artists fought considering they had to fight. The New Deal arts projects were under siege from nigh the moment they arrived on the scene. "[D]uring the seven and a half years that I ran that projection it was attacked by everybody under the lord's day," Holger Cahill remembered. "There was a dead cat coming through the window every few minutes."

Artists and their supporters fought to brand the arts projects permanent. Very soon, though, amidst scrutiny and calumny, they were fighting just to keep them from being shuttered.

Roosevelt came under pressure to rein in spending after the '36 election. Salaries on the projects were slashed. Government spending cuts, in plough, helped unleash a terrible new phase of the Depression in '37, the so-called Roosevelt Recession, spiking unemployment back upward to near 20 percent. Riding the wave of voter disillusionment, Republicans came roaring back and re-took Congress in '38, going on the offensive to gyre dorsum whatsoever they could of the New Deal.

Though minuscule in the telescopic of things, the New Deal art projects were a ready-to-hand symbol for government waste product and the futility of authorities work cosmos in general, which was hated by free marketeers as interference into the labor market. Arts advocates liked to say that the New Bargain art projects had finally connected art to a broad and democratic audition and that art was now valued like any other form of useful labor. While it is fair today to celebrate its successes in that direction, it'due south too important to know that not everyone bought that line, non even at the high point of artist-worker solidarity in the 1930s.

At the time, The Nation summed the role of the New Deal art initiatives in the public discourse like this:

The Federal Art Projects have become the focal point for the continuing attack on the standards and methods of relief symbolized by the Works Progress Administration. The reason is piece of cake to discover. Nobody loves the artist. Ridiculing him or condescending to him is an old American pastime.

An endeavour to pass a bill to create a permanent Federal Arts Bureau, the Java-Pepper Pecker—seen as a proxy for "the defence force of the Left'south formulation of what the New Deal had accomplished and how that achievement should be extended," according to Jonathan Harris—went downwardly in defeat in June 1938 in a 195 to 35 rout.

The End of the Bargain

Hallie Flanagan on CBS Radio for the Federal Theatre of the Air, 1936.

The New Deal arts initiatives were slammed as Soviet propaganda. They were attacked as handouts for lazy artists who couldn't make it on the market. The Hearst press, the Flim-flam News of its twenty-four hour period, was relentless at stirring up resentment with headlines like "Children of the Rich on the WPA Project." Federal One was denounced, above all, for subsidizing "bad art."

And it was in the campaign demonizing the FAP that a sinister force first arrived centerstage, in 1938: the Dies Committee, aka the House Un-American Diplomacy Committee (HUAC). At the hearing in late 1938 about Communist influence in the Federal Theater, Alabama Democrat Joseph Starns infamously grilled project director Hallie Flanagan over whether Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe was a current member of the Communist Party and whether Greek dramatist Euripides "was guilty of teaching grade consciousness." Funny stuff, though Flanagan herself didn't think so: "8 thousand people might lose their jobs considering a Congressional Committee had so pre-judged u.s. that even the classics were 'communistic.'"

Post-state of war, HUAC's anti-Communist witch-hunting would go on to get the means to discipline any kind of public progressive sentiment, vehement the guts out of the labor motion and the eye out of the arts.

Some of the decline of the New Deal art projects amounted to self-inflicted harm. The Communist Party, of form, really was influential in the Artists Union—a mixed approval, bringing an imperfect simply alee-of-its-fourth dimension commitment to fighting racism, on the one mitt, along with an unthinking adherence to the USSR's foreign policy on the other. When Stalin signed a nonaggression pact with Hitler in '39, that split up the Artists Union. Disillusionment and a moving ridge of defections followed. Recriminations about "Communazis" persisted through the art magazines of the '40s (even as the Communist Party itself swung into line backside Roosevelt in the period of the alliance with Stalin, fifty-fifty arguing against strikes in war industries).

But by then, the hour was late anyhow. The radical role of the New Deal was over. FDR was not particularly inclined to fight for unpopular arts relief. When workers went on strike to fight cuts to government arts programs in '38, he explicitly argued, "Participation in these activities past such employees volition be considered insubordination and grounds for dismissal." He was more preoccupied with mollifying big business to meet the demands of rearmament for the impending World War.

In '39, Congress voted to accept the canis familiaris out to shoot it, terminating the The states's already weakened experiment with big-scale back up for artists.

The Relevance Today

WPA mural from the Clarkson S. Fisher Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, Trenton, New Jersey, ca. 1935. (Photo by VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images)

Certainly, we have nothing like the level of sheer organized and rebellious energy in society that existed in the New Bargain period.

On the other manus, the arts were a much smaller economic business at the time. MoMA, the Whitney, and Mellon'south bequest that formed National Gallery of Fine art were all phenomena of the 1930s. The mod "art world" then was only just coalescing.

Every bit the recent letter from Democratic mayors attests, the cultural industries today are a much bigger share of the economic system. Ane of the effects of the neoliberal economic policies that ascertain our immediate history is that they have downplayed manufacturing in favor of tourism, entertainment, and services. Then there is a much larger raw capitalist case for an arts industry bailout.

Simply when it comes to the threat of right-wing forces using arts support every bit the tip of the spear for of a larger demonization of all forms of economic support—that threat, if annihilation, is much more than likely, given the pessimism and extremist migrate of gimmicky politics and the general climate of atomization. The first COVID bailout final year saw Nikki Halley score false-populist points past demonizing the rescue parcel for having crumbs for the arts in information technology. Trump ended last year pairing a demand for $2,000 checks with a demand to cipher out the Smithsonian and the National Gallery.

I don't want to minimize the relevance of the New Deal art projects for today as an inspiration. It's important history, with plenty to inspire in it. And we are in an emergency whose only illustration may well exist the Great Depression.

But I would say that the relevant lesson of the era is that such programs are non only a good idea laying around to be dusted off or a nice affair yous ask for. The history is important: the New Deal fine art projects were born in struggle and they inspired implacable hostility that had far-reaching effects. To take their historical example seriously as a model for the nowadays is to empathise that information technology is adangerous demand—in both ways you lot can mean that.

Information technology is dangerous in a good way because the idea of federal art support threatens the settled ways we remember nearly how fine art works—which is a good thing, since even earlier the nowadays crisis the art system was broken and in need of a new deal of some kind. Merely information technology is dangerous in a bad way in that it makes art a political target. And without organization and the solidarity of much broader social movements, art is a very, very easy target to hit.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay alee of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to become the breaking news, middle-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Source: https://news.artnet.com/opinion/new-deal-art-projects-lessons-1946590

0 Response to "Why Did Some Criticize Fdrs Art Programs While Some Defended Them?"

Post a Comment